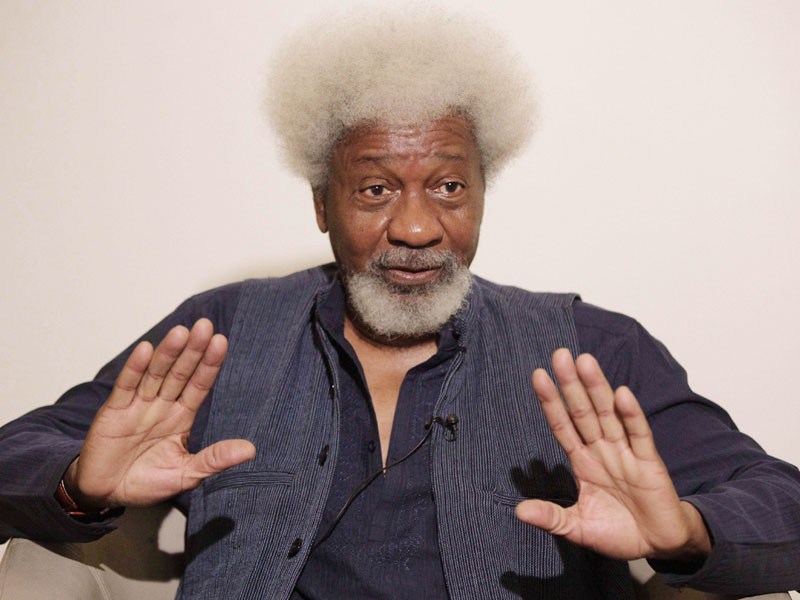

Nigerian nobel laureate Wole Soyinka has spoken on the current agitation for Biafra said it will be better to allow Biafrans to go if they wish to, says the unity of Nigeria is negotiable.

In a recently published article he spoke extensively about the Nigerian nation and the old and renewed agitations for Biafra.

He spoke of the devastating effects of the civil war- caused by the first agitation- and stated that although the agitators at that time were defeated, the agitation wasn’t crushed.

Excerpt:

On July 6, 1967, civil war broke out in Nigeria between the country’s military and the forces of Biafra, an independent republic proclaimed by ex-Nigerian military officer Odumegwu Ojukwu on May 30 of that year. The war killed more than 1 million people, many of whom died from starvation. It ended in January 1970 with the reintegration of Biafra into Nigeria.

Malnutrition, Red Cross, kwashiorkor, relief flights, genocide, the Uli airstrip used by Biafran planes to elude the Nigerian blockade, mercenaries, the Aburi accord that broke down and led to war—these are some of the memory triggers of the Nigerian civil war of secession that we would like to re-assign.

Over a million lives perished—a shameful proportion of them children—mostly through starvation and aerial bombardment. The Nigerian federal government, committed to the doctrine of oneness, had boasted that the conflict would last no longer than three weeks of “police action.” We had learnt much from the politics of other nations, but apparently not from history; the war lasted more than two years.

Tormented by the image of a herd of human lemmings rushing to their doom, as a young writer, I made the “treasonable” statement warning that the secessionist state, Biafra, could never be defeated. The simplistic rendition of that conviction in most minds—certainly in the minds of the then-ruling military and its elite support—was that this applied merely to the physical field of combat. Thus it was regarded as a psychological offensive against the federal side, an attempt to demoralize its soldiers while boosting the war spirit of the enemy. That “enemy” had also boasted that no force in black Africa could defeat them.

My visit to the Biafran enclave in October 1966 resulted in arrest and detention. During interrogation, I insisted that my statement was meant as a counter to the surge of emotive nationalism and a slavish sanctification of colonial boundaries. Biafra was therefore an expression of that rejection and its replacement with a people’s self-constitutive rights. This specific challenge owed its genesis to