As seven abducted women and four children were being taken deeper into Sambisa forest, Aisha Bakari Gombi received a call.

The voice was familiar: an army commander asking her to assemble a group of hunters to track them down.

The voice was familiar: an army commander asking her to assemble a group of hunters to track them down.

The 11 had vanished earlier that day after a group of Boko Haram militants attacked their village, Daggu. Three local people were shot dead and cars, houses and food stores set ablaze.

Daggu is a half-hour drive from Chibok where more than 200 schoolgirls were abducted in April 2014. Both villages are in the region of Borno state in north-eastern Nigeria, which has become all too familiar with such attacks by the world’s deadliest terrorist group.

Boko Haram know me and fear me

Aisha Bakari Gombi

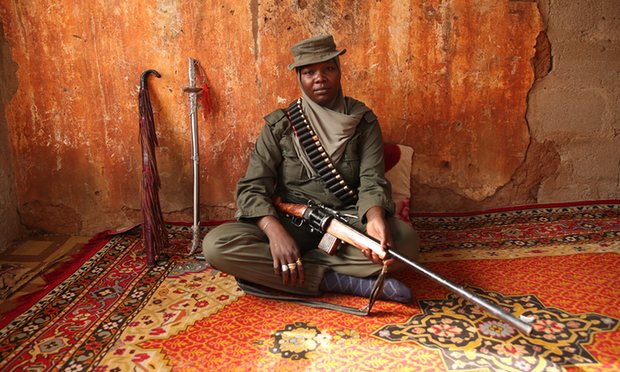

Bakari Gombi grew up near the Sambisa forest, where the extremists still operate despite a military offensive last year that destroyed many of their major camps. She used to hunt antelopes, baboons and guinea fowl with her grandfather. Now she hunts Boko Haram.

There are thousands of hunters in the region who have been enlisted by the military on an ad hoc basis. But Bakari Gombi is one of only a handful of women involved and she has become a heroine for hunters and local people alike. Her gallantry has won her the title “queen hunter”.

The first rescue mission in Daggu failed “because Boko Haram was heavily armed. But we saw where [the girls] are being held,” Bakari Gombi explains the morning after. “We could free them if the military would give us better weapons,” she adds, eyeing the double-barrel shotgun on her lap.

Like many in the rural regions of north-east Nigeria, Bakari Gombi is Muslim but also believes in traditional spirits. One of her rituals is to douse fellow hunters with a secret potion to protect them from bullets.

The 38-year-old leads a command of men aged 15-30 who communicate using sign language, animal sounds and even birdsong.

“Boko Haram know me and fear me,” says Bakari Gombi whose band of hunters has rescued hundreds of men, women and children.

The Nigerian army began recruiting women in 2011 and, while the numbers remain low nationwide, in this region some women have very personal reasons for joining the counterinsurgency. One of those is Hamsat Hassan, whose sister was kidnapped by Boko Haram two years ago. She has not been seen since.

“I couldn’t fire a gun when I asked to join the Hunters’ Association in a town also called Gombi, but all I knew was that I wanted to avenge the people who abducted my sister,” she says.

Hassan’s grandparents look after her seven children so she is available to hunt whenever her services are called on.

While most of the group are volunteers who juggle their commitments with other jobs, Bakari Gombi and Hassan are among the 228 male and female hunters who were recruited on a more formal basis last year by a local government official.

But by October the 10,000 naira (£25) allowances paid to the hunters had stopped. Two months later most of the team had pulled out of the programme, though some, including Bakari Gombi and Hassan, remained committed to the fight.